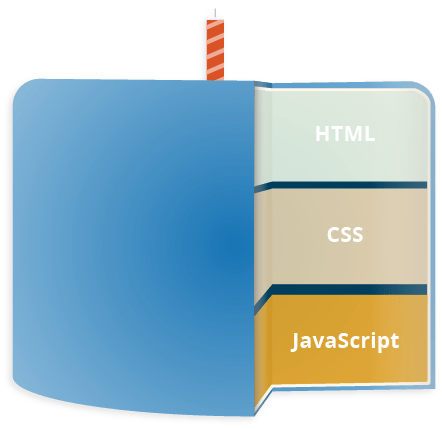

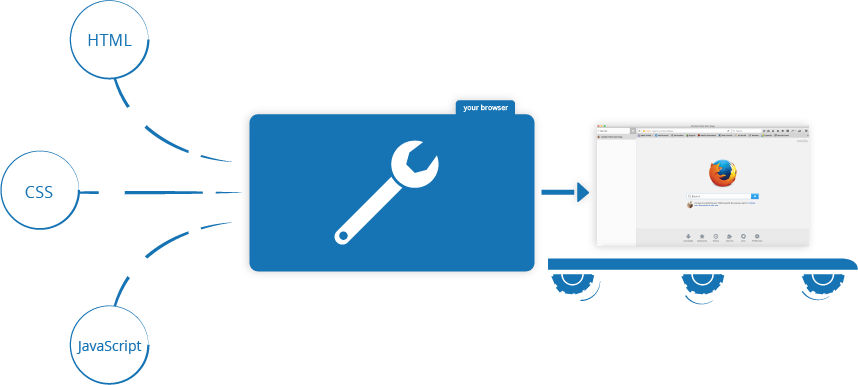

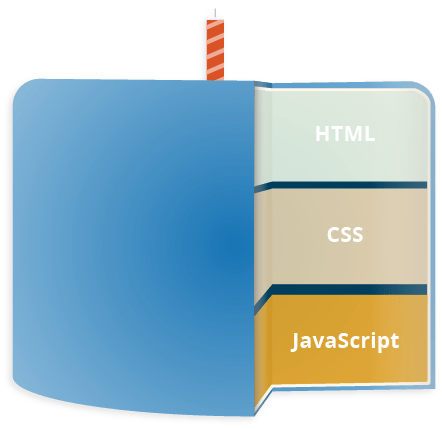

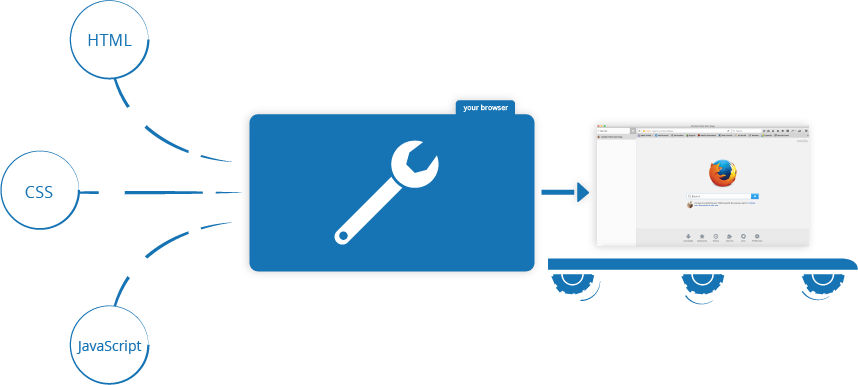

JavaScript is a scripting or programming language that allows you to implement complex features on web pages — every time a web page does more than just sit there and display static information for you to look at — displaying timely content updates, interactive maps, animated 2D/3D graphics, scrolling video jukeboxes, etc. — you can bet that JavaScript is probably involved. It is the third layer of the layer cake of standard web technologies, two of which (HTML and CSS) we have covered in much more detail in other parts of the Learning Area.

- HTML is the markup language that we use to structure and give meaning to our web content, for example defining paragraphs, headings, and data tables, or embedding images and videos in the page.

- CSS is a language of style rules that we use to apply styling to our HTML content, for example setting background colors and fonts, and laying out our content in multiple columns.

- JavaScript is a scripting language that enables you to create dynamically updating content, control multimedia, animate images, and pretty much everything else. (Okay, not everything, but it is amazing what you can achieve with a few lines of JavaScript code.)

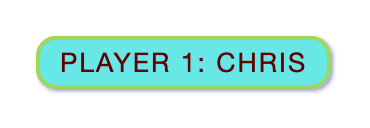

The three layers build on top of one another nicely. Let's take a button as an example. We can mark it up using HTML to give it structure and purpose:

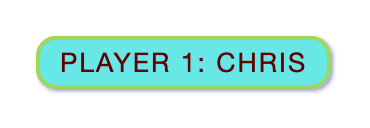

<button type="button">Player 1: Chris</button>

Then we can add some CSS into the mix to get it looking nice:

button {

font-family: "helvetica neue", helvetica, sans-serif;

letter-spacing: 1px;

text-transform: uppercase;

border: 2px solid rgb(200 200 0 / 60%);

background-color: rgb(0 217 217 / 60%);

color: rgb(100 0 0 / 100%);

box-shadow: 1px 1px 2px rgb(0 0 200 / 40%);

border-radius: 10px;

padding: 3px 10px;

cursor: pointer;

}

And finally, we can add some JavaScript to implement dynamic behavior:

const button = document.querySelector("button");

button.addEventListener("click", updateName);

function updateName() {

const name = prompt("Enter a new name");

button.textContent = `Player 1: ${name}`;

}

Try clicking on this last version of the text label to see what happens (note also that you can find this demo on GitHub — see the source code, or run it live)!

JavaScript can do a lot more than that — let's explore what in more detail.

The core client-side JavaScript language consists of some common programming features that allow you to do things like:

- Store useful values inside variables. In the above example for instance, we ask for a new name to be entered then store that name in a variable called

name. - Operations on pieces of text (known as "strings" in programming). In the above example we take the string "Player 1: " and join it to the

name variable to create the complete text label, e.g. "Player 1: Chris". - Running code in response to certain events occurring on a web page. We used a

click event in our example above to detect when the label is clicked and then run the code that updates the text label. - And much more!

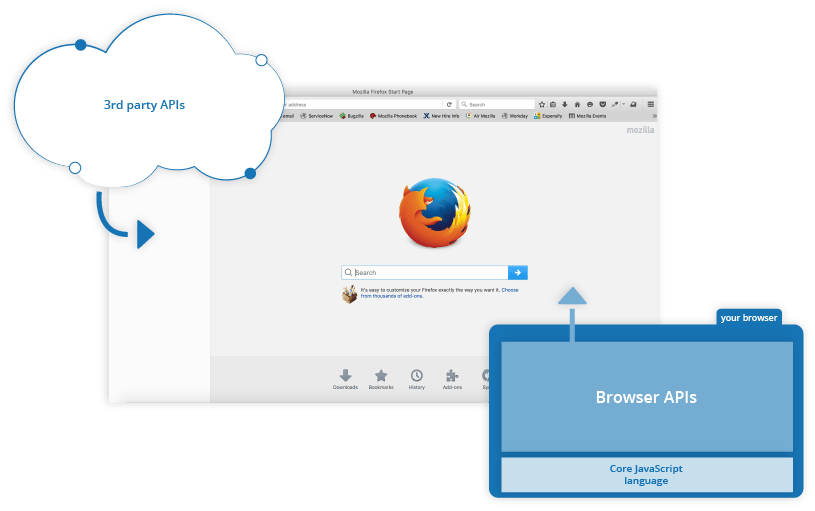

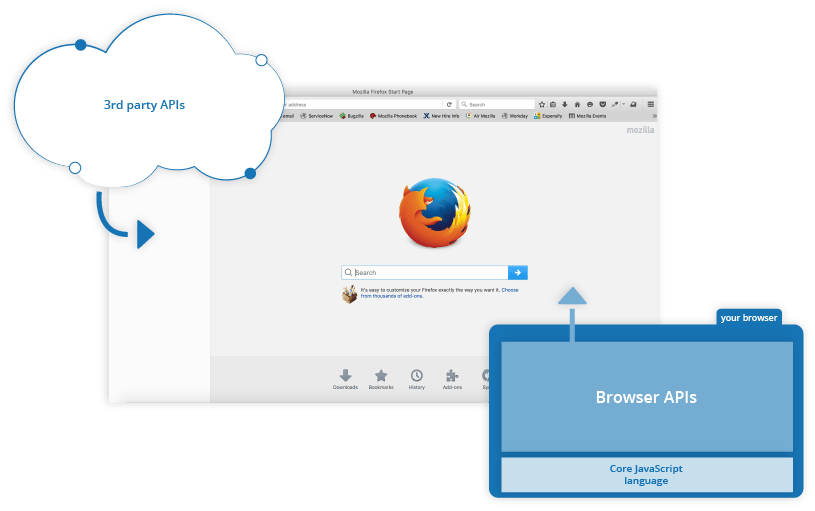

What is even more exciting however is the functionality built on top of the client-side JavaScript language. So-called Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) provide you with extra superpowers to use in your JavaScript code.

APIs are ready-made sets of code building blocks that allow a developer to implement programs that would otherwise be hard or impossible to implement. They do the same thing for programming that ready-made furniture kits do for home building — it is much easier to take ready-cut panels and screw them together to make a bookshelf than it is to work out the design yourself, go and find the correct wood, cut all the panels to the right size and shape, find the correct-sized screws, and then put them together to make a bookshelf.

They generally fall into two categories.

Browser APIs are built into your web browser, and are able to expose data from the surrounding computer environment, or do useful complex things. For example:

- The

DOM (Document Object Model) API allows you to manipulate HTML and CSS, creating, removing and changing HTML, dynamically applying new styles to your page, etc. Every time you see a popup window appear on a page, or some new content displayed (as we saw above in our simple demo) for example, that's the DOM in action. - The

Geolocation API retrieves geographical information. This is how Google Maps is able to find your location and plot it on a map. - The

Canvas and WebGL APIs allow you to create animated 2D and 3D graphics. People are doing some amazing things using these web technologies — see Chrome Experiments and webglsamples. - Audio and Video APIs like

HTMLMediaElement and WebRTC allow you to do really interesting things with multimedia, such as play audio and video right in a web page, or grab video from your web camera and display it on someone else's computer (try our simple Snapshot demo to get the idea).

Note: Many of the above demos won't work in an older browser — when experimenting, it's a good idea to use a modern browser like Firefox, Chrome, Edge or Opera to run your code in. You will need to consider cross browser testing in more detail when you get closer to delivering production code (i.e. real code that real customers will use).

Third party APIs are not built into the browser by default, and you generally have to grab their code and information from somewhere on the Web. For example:

Note: These APIs are advanced, and we'll not be covering any of these in this module. You can find out much more about these in our Client-side web APIs module.

There's a lot more available, too! However, don't get over excited just yet. You won't be able to build the next Facebook, Google Maps, or Instagram after studying JavaScript for 24 hours — there are a lot of basics to cover first. And that's why you're here — let's move on!

Here we'll actually start looking at some code, and while doing so, explore what actually happens when you run some JavaScript in your page.

Let's briefly recap the story of what happens when you load a web page in a browser (first talked about in our How CSS works article). When you load a web page in your browser, you are running your code (the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript) inside an execution environment (the browser tab). This is like a factory that takes in raw materials (the code) and outputs a product (the web page).

A very common use of JavaScript is to dynamically modify HTML and CSS to update a user interface, via the Document Object Model API (as mentioned above). Note that the code in your web documents is generally loaded and executed in the order it appears on the page. Errors may occur if JavaScript is loaded and run before the HTML and CSS that it is intended to modify. You will learn ways around this later in the article, in the Script loading strategies section.

Each browser tab has its own separate bucket for running code in (these buckets are called "execution environments" in technical terms) — this means that in most cases the code in each tab is run completely separately, and the code in one tab cannot directly affect the code in another tab — or on another website. This is a good security measure — if this were not the case, then pirates could start writing code to steal information from other websites, and other such bad things.

Note: There are ways to send code and data between different websites/tabs in a safe manner, but these are advanced techniques that we won't cover in this course.

When the browser encounters a block of JavaScript, it generally runs it in order, from top to bottom. This means that you need to be careful what order you put things in. For example, let's return to the block of JavaScript we saw in our first example:

const button = document.querySelector("button");

button.addEventListener("click", updateName);

function updateName() {

const name = prompt("Enter a new name");

button.textContent = `Player 1: ${name}`;

}

Here we are selecting a button (line 1), then attaching an event listener to it (line 3) so that when the button is clicked, the updateName() code block (lines 5–8) is run. The updateName() code block (these types of reusable code blocks are called "functions") asks the user for a new name, and then inserts that name into the button text to update the display.

If you swapped the order of the first two lines of code, it would no longer work — instead, you'd get an error returned in the browser developer console — Uncaught ReferenceError: Cannot access 'button' before initialization. This means that the button object has not been initialized yet, so we can't add an event listener to it.

Note: This is a very common error — you need to be careful that the objects referenced in your code exist before you try to do stuff to them.

You might hear the terms interpreted and compiled in the context of programming. In interpreted languages, the code is run from top to bottom and the result of running the code is immediately returned. You don't have to transform the code into a different form before the browser runs it. The code is received in its programmer-friendly text form and processed directly from that.

Compiled languages on the other hand are transformed (compiled) into another form before they are run by the computer. For example, C/C++ are compiled into machine code that is then run by the computer. The program is executed from a binary format, which was generated from the original program source code.

JavaScript is a lightweight interpreted programming language. The web browser receives the JavaScript code in its original text form and runs the script from that. From a technical standpoint, most modern JavaScript interpreters actually use a technique called just-in-time compiling to improve performance; the JavaScript source code gets compiled into a faster, binary format while the script is being used, so that it can be run as quickly as possible. However, JavaScript is still considered an interpreted language, since the compilation is handled at run time, rather than ahead of time.

There are advantages to both types of language, but we won't discuss them right now.

You might also hear the terms server-side and client-side code, especially in the context of web development. Client-side code is code that is run on the user's computer — when a web page is viewed, the page's client-side code is downloaded, then run and displayed by the browser. In this module we are explicitly talking about client-side JavaScript.

Server-side code on the other hand is run on the server, then its results are downloaded and displayed in the browser. Examples of popular server-side web languages include PHP, Python, Ruby, ASP.NET, and even JavaScript! JavaScript can also be used as a server-side language, for example in the popular Node.js environment — you can find out more about server-side JavaScript in our Dynamic Websites – Server-side programming topic.

The word dynamic is used to describe both client-side JavaScript, and server-side languages — it refers to the ability to update the display of a web page/app to show different things in different circumstances, generating new content as required. Server-side code dynamically generates new content on the server, e.g. pulling data from a database, whereas client-side JavaScript dynamically generates new content inside the browser on the client, e.g. creating a new HTML table, filling it with data requested from the server, then displaying the table in a web page shown to the user. The meaning is slightly different in the two contexts, but related, and both approaches (server-side and client-side) usually work together.

A web page with no dynamically updating content is referred to as static — it just shows the same content all the time.

JavaScript is applied to your HTML page in a similar manner to CSS. Whereas CSS uses <link> elements to apply external stylesheets and <style> elements to apply internal stylesheets to HTML, JavaScript only needs one friend in the world of HTML — the <script> element. Let's learn how this works.

- First of all, make a local copy of our example file apply-javascript.html. Save it in a directory somewhere sensible.

- Open the file in your web browser and in your text editor. You'll see that the HTML creates a simple web page containing a clickable button.

- Next, go to your text editor and add the following in your head — just before your closing

</head> tag: - Now we'll add some JavaScript inside our

<script> element to make the page do something more interesting — add the following code just below the "// JavaScript goes here" line:document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", () => {

function createParagraph() {

const para = document.createElement("p");

para.textContent = "You clicked the button!";

document.body.appendChild(para);

}

const buttons = document.querySelectorAll("button");

for (const button of buttons) {

button.addEventListener("click", createParagraph);

}

});

- Save your file and refresh the browser — now you should see that when you click the button, a new paragraph is generated and placed below.

Note: If your example doesn't seem to work, go through the steps again and check that you did everything right. Did you save your local copy of the starting code as a .html file? Did you add your <script> element just before the </head> tag? Did you enter the JavaScript exactly as shown? JavaScript is case sensitive, and very fussy, so you need to enter the syntax exactly as shown, otherwise it may not work.

This works great, but what if we wanted to put our JavaScript in an external file? Let's explore this now.

- First, create a new file in the same directory as your sample HTML file. Call it

script.js — make sure it has that .js filename extension, as that's how it is recognized as JavaScript. - Replace your current

<script> element with the following:<script src="script.js" defer></script>

- Inside

script.js, add the following script:function createParagraph() {

const para = document.createElement("p");

para.textContent = "You clicked the button!";

document.body.appendChild(para);

}

const buttons = document.querySelectorAll("button");

for (const button of buttons) {

button.addEventListener("click", createParagraph);

}

- Save and refresh your browser, and you should see the same thing! It works just the same, but now we've got our JavaScript in an external file. This is generally a good thing in terms of organizing your code and making it reusable across multiple HTML files. Plus, the HTML is easier to read without huge chunks of script dumped in it.

Note that sometimes you'll come across bits of actual JavaScript code living inside HTML. It might look something like this:

function createParagraph() {

const para = document.createElement("p");

para.textContent = "You clicked the button!";

document.body.appendChild(para);

}

<button onclick="createParagraph()">Click me!</button>

You can try this version of our demo below.

This demo has exactly the same functionality as in the previous two sections, except that the <button> element includes an inline onclick handler to make the function run when the button is pressed.

Please don't do this, however. It is bad practice to pollute your HTML with JavaScript, and it is inefficient — you'd have to include the onclick="createParagraph()" attribute on every button you want the JavaScript to apply to.

Instead of including JavaScript in your HTML, use a pure JavaScript construct. The querySelectorAll() function allows you to select all the buttons on a page. You can then loop through the buttons, assigning a handler for each using addEventListener(). The code for this is shown below:

const buttons = document.querySelectorAll("button");

for (const button of buttons) {

button.addEventListener("click", createParagraph);

}

This might be a bit longer than the onclick attribute, but it will work for all buttons — no matter how many are on the page, nor how many are added or removed. The JavaScript does not need to be changed.

Note: Try editing your version of apply-javascript.html and add a few more buttons into the file. When you reload, you should find that all of the buttons when clicked will create a paragraph. Neat, huh?

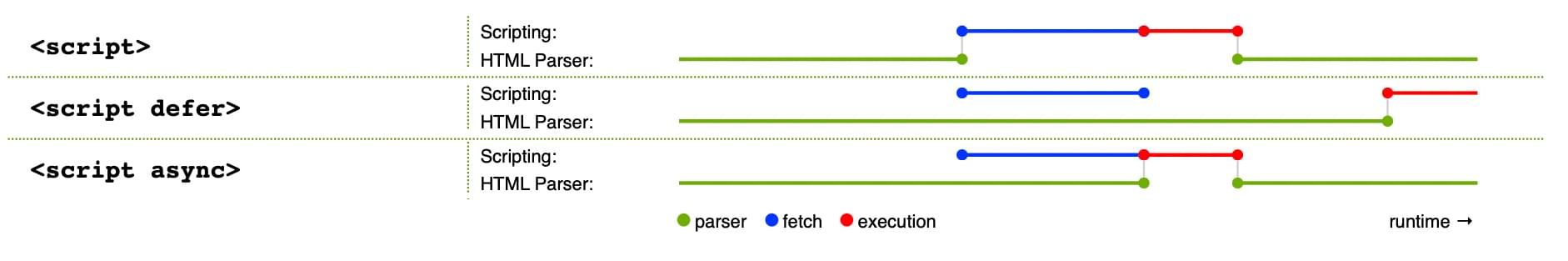

There are a number of issues involved with getting scripts to load at the right time. Nothing is as simple as it seems! A common problem is that all the HTML on a page is loaded in the order in which it appears. If you are using JavaScript to manipulate elements on the page (or more accurately, the Document Object Model), your code won't work if the JavaScript is loaded and parsed before the HTML you are trying to do something to.

In the above code examples, in the internal and external examples the JavaScript is loaded and run in the head of the document, before the HTML body is parsed. This could cause an error, so we've used some constructs to get around it.

In the internal example, you can see this structure around the code:

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", () => {

});

This is an event listener, which listens for the browser's DOMContentLoaded event, which signifies that the HTML body is completely loaded and parsed. The JavaScript inside this block will not run until after that event is fired, therefore the error is avoided (you'll learn about events later in the course).

In the external example, we use a more modern JavaScript feature to solve the problem, the defer attribute, which tells the browser to continue downloading the HTML content once the <script> tag element has been reached.

<script src="script.js" defer></script>

In this case both the script and the HTML will load simultaneously and the code will work.

Note: In the external case, we did not need to use the DOMContentLoaded event because the defer attribute solved the problem for us. We didn't use the defer solution for the internal JavaScript example because defer only works for external scripts.

An old-fashioned solution to this problem used to be to put your script element right at the bottom of the body (e.g. just before the </body> tag), so that it would load after all the HTML has been parsed. The problem with this solution is that loading/parsing of the script is completely blocked until the HTML DOM has been loaded. On larger sites with lots of JavaScript, this can cause a major performance issue, slowing down your site.

async and defer

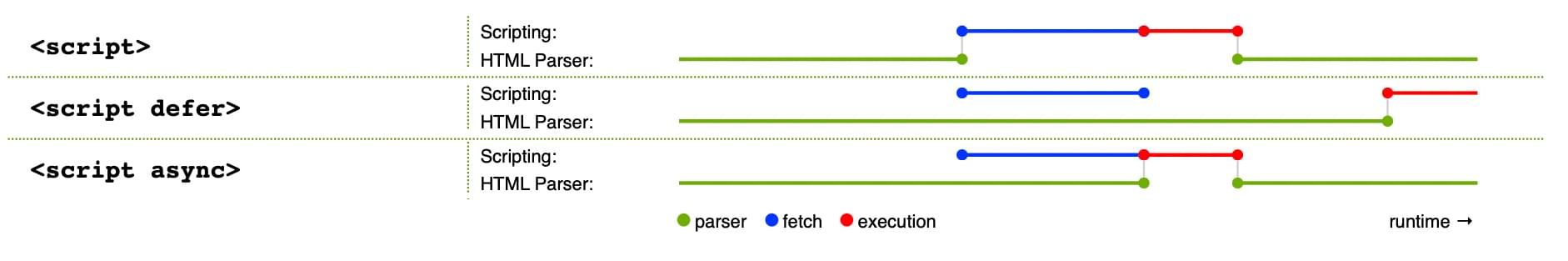

There are actually two modern features we can use to bypass the problem of the blocking script — async and defer (which we saw above). Let's look at the difference between these two.

Scripts loaded using the async attribute will download the script without blocking the page while the script is being fetched. However, once the download is complete, the script will execute, which blocks the page from rendering. This means that the rest of the content on the web page is prevented from being processed and displayed to the user until the script finishes executing. You get no guarantee that scripts will run in any specific order. It is best to use async when the scripts in the page run independently from each other and depend on no other script on the page.

Scripts loaded with the defer attribute will load in the order they appear on the page. They won't run until the page content has all loaded, which is useful if your scripts depend on the DOM being in place (e.g. they modify one or more elements on the page).

Here is a visual representation of the different script loading methods and what that means for your page:

This image is from the HTML spec, copied and cropped to a reduced version, under CC BY 4.0 license terms.

For example, if you have the following script elements:

<script async src="js/vendor/jquery.js"></script>

<script async src="js/script2.js"></script>

<script async src="js/script3.js"></script>

You can't rely on the order the scripts will load in. jquery.js may load before or after script2.js and script3.js and if this is the case, any functions in those scripts depending on jquery will produce an error because jquery will not be defined at the time the script runs.

async should be used when you have a bunch of background scripts to load in, and you just want to get them in place as soon as possible. For example, maybe you have some game data files to load, which will be needed when the game actually begins, but for now you just want to get on with showing the game intro, titles, and lobby, without them being blocked by script loading.

Scripts loaded using the defer attribute (see below) will run in the order they appear in the page and execute them as soon as the script and content are downloaded:

<script defer src="js/vendor/jquery.js"></script>

<script defer src="js/script2.js"></script>

<script defer src="js/script3.js"></script>

In the second example, we can be sure that jquery.js will load before script2.js and script3.js and that script2.js will load before script3.js. They won't run until the page content has all loaded, which is useful if your scripts depend on the DOM being in place (e.g. they modify one or more elements on the page).

To summarize:

async and defer both instruct the browser to download the script(s) in a separate thread, while the rest of the page (the DOM, etc.) is downloading, so the page loading is not blocked during the fetch process.- scripts with an

async attribute will execute as soon as the download is complete. This blocks the page and does not guarantee any specific execution order. - scripts with a

defer attribute will load in the order they are in and will only execute once everything has finished loading. - If your scripts should be run immediately and they don't have any dependencies, then use

async. - If your scripts need to wait for parsing and depend on other scripts and/or the DOM being in place, load them using

defer and put their corresponding <script> elements in the order you want the browser to execute them.

As with HTML and CSS, it is possible to write comments into your JavaScript code that will be ignored by the browser, and exist to provide instructions to your fellow developers on how the code works (and you, if you come back to your code after six months and can't remember what you did). Comments are very useful, and you should use them often, particularly for larger applications. There are two types:

- A single line comment is written after a double forward slash (//), e.g.

- A multi-line comment is written between the strings /* and */, e.g.

So for example, we could annotate our last demo's JavaScript with comments like so:

function createParagraph() {

const para = document.createElement("p");

para.textContent = "You clicked the button!";

document.body.appendChild(para);

}

const buttons = document.querySelectorAll("button");

for (const button of buttons) {

button.addEventListener("click", createParagraph);

}

Note: In general more comments are usually better than less, but you should be careful if you find yourself adding lots of comments to explain what variables are (your variable names perhaps should be more intuitive), or to explain very simple operations (maybe your code is overcomplicated).

So there you go, your first step into the world of JavaScript. We've begun with just theory, to start getting you used to why you'd use JavaScript and what kind of things you can do with it. Along the way, you saw a few code examples and learned how JavaScript fits in with the rest of the code on your website, amongst other things.

JavaScript may seem a bit daunting right now, but don't worry — in this course, we will take you through it in simple steps that will make sense going forward. In the next article, we will plunge straight into the practical, getting you to jump straight in and build your own JavaScript examples.

I Background

1 Before you buy the book

9

11

1.1 About the content . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.2 Previewing and buying this book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.3 About the author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.4 Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

2 FAQ: book and supplementary material

15

2.1 How to read this book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

2.2 I own a digital version . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16

2.3 I own the print version . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16

2.4 Notations and conventions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

17

3 History and evolution of JavaScript

19

3.1 How JavaScript was created . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

3.2 Standardizing JavaScript . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

3.3 Timeline of ECMAScript versions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

3.4 Ecma Technical Committee 39 (TC39) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

3.5 The TC39 process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

3.6 FAQ: TC39 process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

3.7 Evolving JavaScript: Don’t break the web . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

4 New JavaScript features

25

4.1 New in ECMAScript 2022 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

4.2 New in ECMAScript 2021 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

26

4.3 New in ECMAScript 2020 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

27

4.4 New in ECMAScript 2019 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

4.5 New in ECMAScript 2018 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

4.6 New in ECMAScript 2017 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30

4.7 New in ECMAScript 2016 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30

4.8 Source of this chapter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30

5 FAQ: JavaScript

31

5.1 What are good references for JavaScript? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

31

5.2 How do I find out what JavaScript features are supported where? . . . .

31

5.3 Where can I look up what features are planned for JavaScript? . . . . . . 32 34

CONTENTS

5.4 Why does JavaScript fail silently so often? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32 5.5 Why can’t we clean up JavaScript, by removing quirks and outdated fea-

tures? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

5.6 How can I quickly try out a piece of JavaScript code? . . . . . . . . . . . 32

II First steps

33

6 Using JavaScript: the big picture

35

6.1 What are you learning in this book? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

6.2 The structure of browsers and Node.js . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

6.3 JavaScript references . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

6.4 Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

7 Syntax

37

7.1 An overview of JavaScript’s syntax . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

7.2 (Advanced) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

45

7.3 Identifiers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

45

7.4 Statement vs. expression . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

7.5 Ambiguous syntax . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

48

7.6 Semicolons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

7.7 Automatic semicolon insertion (ASI) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

50

7.8 Semicolons: best practices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

7.9 Strict mode vs. sloppy mode . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

52

8 Consoles: interactive JavaScript command lines

55

8.1 Trying out JavaScript code . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

55

8.2 The console.* API: printing data and more . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

57

9 Assertion API

61

9.1 Assertions in software development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

61

9.2 How assertions are used in this book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

61

9.3 Normal comparison vs. deep comparison . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

62

9.4 Quick reference: module assert . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

63

10 Gett

ing started with quizzes and exercises

67

10.1

Quizzes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

10.2

Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

10.3

Unit tests in JavaScript . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

68

III Variables and values 11 Variables and assignment

73

75

11.1 let . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

11.2 const . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

11.3 Deciding between const and let . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

11.4 The scope of a variable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

11.5 (Advanced) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

11.6 Terminology: static vs. dynamic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79CONTENTS

5

11.7 Global variables and the global object . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

11.8 Declarations: scope and activation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

11.9 Closures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

12 Values

89

12.1 What’s a type? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

12.2 JavaScript’s type hierarchy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

12.3 The types of the language specification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

12.4 Primitive values vs. objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

12.5 The operators typeof and instanceof: what’s the type of a value? . . . . 94

12.6 Classes and constructor functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

12.7 Converting between types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

13 Operators

99

13.1 Making sense of operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

13.2 The plus operator (+) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

13.3 Assignment operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

13.4 Equality: == vs. === . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

13.5 Ordering operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

13.6 Various other operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

IV Primitive values

107

14 The non-values undefined and null

109

14.1 undefined vs. null . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

109

14.2 Occurrences of undefined and null . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

110

14.3 Checking for undefined or null . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

111

14.4 The nullish coalescing operator (??) for default values [ES2020] . . . . . .

111

14.5 undefined and null don’t have properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

114

14.6 The history of undefined and null . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

115

15 Booleans

117

15.1 Converting to boolean . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

117

15.2 Falsy and truthy values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

118

15.3 Truthiness-based existence checks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

119

15.4 Conditional operator (? :) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

121

15.5 Binary logical operators: And (x && y), Or (x || y) . . . . . . . . . . . .

122

15.6 Logical Not (!) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

124

16 Numbers

125

16.1 Numbers are used for both floating point numbers and integers . . . . .

126

16.2 Number literals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

126

16.3 Arithmetic operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

128

16.4 Converting to number . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

131

16.5 Error values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

132

16.6 The precision of numbers: careful with decimal fractions . . . . . . . . .

134

16.7 (Advanced) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

16.8 Background: floating point precision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1356

CONTENTS

16.9 Integer numbers in JavaScript . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 136

16.10Bitwise operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139

16.11 Quick reference: numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142

17 Math

147

17.1 Data properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147

17.2 Exponents, roots, logarithms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

17.3 Rounding . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149

17.4 Trigonometric Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

17.5 Various other functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152

17.6 Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

18 Bigints – arbitrary-precision integers [ES2020] (advanced)

155

18.1 Why bigints? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

156

18.2 Bigints . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

156

18.3 Bigint literals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

158

18.4 Reusing number operators for bigints (overloading) . . . . . . . . . . . .

158

18.5 The wrapper constructor BigInt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

162

18.6 Coercing bigints to other primitive types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

164

18.7 TypedArrays and DataView operations for 64-bit values . . . . . . . . . .

164

18.8 Bigints and JSON . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

164

18.9 FAQ: Bigints . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

165

19 Unicode – a brief introduction (advanced)

167

19.1 Code points vs. code units . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

167

19.2 Encodings used in web development: UTF-16 and UTF-8 . . . . . . . . .

170

19.3 Grapheme clusters – the real characters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

171

20 Strings

173

20.1 Cheat sheet: strings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

174

20.2 Plain string literals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

176

20.3 Accessing JavaScript characters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

177

20.4 String concatenation via + . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

178

20.5 Converting to string . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

178

20.6 Comparing strings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

180

20.7 Atoms of text: code points, JavaScript characters, grapheme clusters . . .

180

20.8 Quick reference: Strings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

183

21 Using template literals and tagged templates

191

21.1 Disambiguation: “template” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

191

21.2 Template literals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

192

21.3 Tagged templates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

193

21.4 Examples of tagged templates (as provided via libraries) . . . . . . . . .

195

21.5 Raw string literals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

196

21.6 (Advanced) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

196

21.7 Multiline template literals and indentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

196

21.8 Simple templating via template literals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 198

22 Symbols

201CONTENTS

7

22.1 Symbols are primitives that are also like objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201

22.2 The descriptions of symbols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 202

22.3 Use cases for symbols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 202

22.4 Publicly known symbols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 205

22.5 Converting symbols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 206

V Control flow and data flow

209

23 Control flow statements

211

23.1 Controlling loops: break and continue . . . .

...............

212

23.2 Conditions of control flow statements . . . . .

...............

213

23.3 if statements [ES1] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

214

23.4 switch statements [ES3] . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

215

23.5 while loops [ES1] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

217

23.6 do-while loops [ES3] . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

218

23.7 for loops [ES1] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

218

23.8 for-of loops [ES6] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

220

23.9 for-await-of loops [ES2018] . . . . . . . . .

...............

221

23.10for-in loops (avoid) [ES1] . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

221

23.11 Recomendations for looping . . . . . . . . . .

...............

222

24 Exception handling

223

24.1 Motivation: throwing and catching exceptions

...............

223

24.2 throw . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

224

24.3 The try statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

225

24.4 Error and its subclasses . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

227

24.5 Chaining errors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

230

25 Callable values

233

25.1 Kinds of functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

234

25.2 Ordinary functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

234

25.3 Specialized functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

237

25.4 Summary: kinds of callable values . . . . . . .

...............

242

25.5 Returning values from functions and methods

...............

243

25.6 Parameter handling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

244

25.7 Methods of functions: .call(), .apply(), .bin

d() . . . . . . . . . . . . .

248

26 Evaluating code dynamically: eval(), new Functio

n() (advanced)

251

26.1 eval() . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

251

26.2 new Function() . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

252

26.3 Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

252

VI Modularity

255

27 Modules

257

27.1 Cheat sheet: modules . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...............

258

27.2 JavaScript source code formats . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259

27.3 Before we had modules, we had scripts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2598

CONTENTS

27.4 Module systems created prior to ES6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

27.5 ECMAScript modules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 263

27.6 Named exports and imports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 263

27.7 Default exports and imports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 266

27.8 More details on exporting and importing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 268

27.9 npm packages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 269

27.10Naming modules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271

27.11 Module specifiers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 272

27.12import.meta – metadata for the current module [ES2020] . . . . . . . . . 274

27.13Loading modules dynamically via import() [ES2020] (advanced) . . . . 275

27.14Top-level await in modules [ES2022] (advanced) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 278

27.15Polyfills: emulating native web platform features (advanced) . . . . . . . 280

28 Objects

283

28.1 Cheat sheet: objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 284

28.2 What is an object? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 287

28.3 Fixed-layout objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 288

28.4 Spreading into object literals (...) [ES2018] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 291

28.5 Methods and the special variable this . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 294

28.6 Optional chaining for property getting and method calls [ES2020] (advanced) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 300

28.7 Dictionary objects (advanced) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 304

28.8 Property attributes and freezing objects (advanced) . . . . . . . . . . . . 313

28.9 Prototype chains . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 314

28.10FAQ: objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 320

29 Classes [ES6]

321

29.1 Cheat sheet: classes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 322

29.2 The essentials of classes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 324

29.3 The internals of classes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 333

29.4 Prototype members of classes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 339

29.5 Instance members of classes [ES2022] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 342

29.6 Static members of classes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 348

29.7 Subclassing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 357

29.8 The methods and accessors of Object.prototype (advanced) . . . . . . . 364

29.9 FAQ: classes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 371

30 Where are the remaining chapters?

373Part I Background

9Chapter 1

Before you buy the book

Contents

1.1 About the content . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.1.1 What’s in this book? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.1.2 What is not covered by this book? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.1.3 Isn’t this book too long for impatient people? . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.2 Previewing and buying this book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.2.1 How can I preview the book, the exercises, and the quizzes? . 12

1.2.2 How can I buy a digital version of this book? . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.2.3 How can I buy the print version of this book? . . . . . . . . . 12

1.3 About the author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.4 Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

1.1 About the content

1.1.1 What’s in this book?

This book makes JavaScript less challenging to learn for newcomers by offering a modern view that is as consistent as possible.

Highlights:

• Get started quickly by initially focusing on modern features.

• Test-driven exercises and quizzes available for most chapters.

• Covers all essential features of JavaScript, up to and including ES2022.

• Optional advanced sections let you dig deeper.

No prior knowledge of JavaScript is required, but you should know how to program.

1112

1.1.2 What is not covered by this book?

1 Before you buy the book

• Some advanced language features are not explained, but references to appropri- ate material are provided – for example, to my other JavaScript books at Explor- ingJS.com, which are free to read online.

• This book deliberately focuses on the language. Browser-only features, etc. are not described.

1.1.3 Isn’t this book too long for impatient people?

There are several ways in which you can read this book. One of them involves skipping much of the content in order to get started quickly. For details, see §2.1.1 “In which order should I read the content in this book?”.

1.2 Previewing and buying this book

1.2.1 How can I preview the book, the exercises, and the quizzes?

Go to the homepage of this book:

• All essential chapters of this book are free to read online.

• The first half of the test-driven exercises can be downloaded.

• The first half of the quizzes can be tried online.

1.2.2 How can I buy a digital version of this book?

There are two digital versions of JavaScript for impatient programmers:

• Ebooks: PDF, EPUB, MOBI, HTML (all without DRM)

• Ebooks plus exercises and quizzes

The home page of this book describes how you can buy them.

1.2.3 How can I buy the print version of this book?

The print version of JavaScript for impatient programmers is available on Amazon.

1.3 About the author

Dr. Axel Rauschmayer specializes in JavaScript and web development. He has been de- veloping web applications since 1995. In 1999, he was technical manager at a German internet startup that later expanded internationally. In 2006, he held his first talk on Ajax. In 2010, he received a PhD in Informatics from the University of Munich.

Since 2011, he has been blogging about web development at 2ality.com and has written several books on JavaScript. He has held trainings and talks for companies such as eBay, Bank of America, and O’Reilly Media.

He lives in Munich, Germany.13

1.4 Acknowledgements

1.4 Acknowledgements

• Cover by Fran Caye

• Parts of this book were edited by Adaobi Obi Tulton.

• Thanks for answering questions, discussing language topics, etc.:

– Allen Wirfs-Brock (@awbjs)

– Benedikt Meurer (@bmeurer)

– Brian Terlson (@bterlson)

– Daniel Ehrenberg (@littledan)

– Jordan Harband (@ljharb)

– Maggie Johnson-Pint (@maggiepint)

– Mathias Bynens (@mathias)

– Myles Borins (@MylesBorins)

– Rob Palmer (@robpalmer2)

– Šime Vidas (@simevidas)

– And many others

• Thanks for reviewing:

– Johannes Weber (@jowe) [Generated: 2022-01-03 14:16]14

1 Before you buy the bookChapter 2

FAQ: book and supplementary material

Contents

2.1 How to read this book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

2.1.1 In which order should I read the content in this book? . . . . . 15

2.1.2 Why are some chapters and sections marked with “(advanced)”? 16

2.1.3 Why are some chapters marked with “(bonus)”? . . . . . . . . 16

2.2 I own a digital version . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

2.2.1 How do I submit feedback and corrections? . . . . . . . . . . 16

2.2.2 How do I get updates for the downloads I bought at Payhip? . 16

2.2.3 Can I upgrade from package “Ebooks” to package “Ebooks + exercises + quizzes”? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

2.3 I own the print version . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

2.3.1 Can I get a discount for a digital version? . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

2.3.2 Can I submit an error or see submitted errors? . . . . . . . . . 17

2.3.3 Is there an online list with the URLs in this book? . . . . . . . 17

2.4 Notations and conventions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

2.4.1 What is a type signature? Why am I seeing static types in this book? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

2.4.2 What do the notes with icons mean? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

This chapter answers questions you may have and gives tips for reading this book.

2.1 How to read this book

2.1.1 In which order should I read the content in this book?

This book is three books in one:

• You can use it to get started with JavaScript as quickly as possible. This “mode” is for impatient people:

1516

2 FAQ: book and supplementary material

– Start reading with §6 “Using JavaScript: the big picture”.

– Skip all chapters and sections marked as “advanced”, and all quick refer- ences.

• It gives you a comprehensive look at current JavaScript. In this “mode”, you read everything and don’t skip advanced content and quick references.

• It serves as a reference. If there is a topic that you are interested in, you can find information on it via the table of contents or via the index. Due to basic and ad- vanced content being mixed, everything you need is usually in a single location.

The quizzes and exercises play an important part in helping you practice and retain what you have learned.

2.1.2 Why are some chapters and sections marked with “(advanced)”?

Several chapters and sections are marked with “(advanced)”. The idea is that you can initially skip them. That is, you can get a quick working knowledge of JavaScript by only reading the basic (non-advanced) content.

As your knowledge evolves, you can later come back to some or all of the advanced content.

2.1.3 Why are some chapters marked with “(bonus)”?

The bonus chapters are only available in the paid versions of this book (print and ebook). They are listed in the full table of contents.

2.2 I own a digital version

2.2.1 How do I submit feedback and corrections?

The HTML version of this book (online, or ad-free archive in the paid version) has a link at the end of each chapter that enables you to give feedback.

2.2.2 How do I get updates for the downloads I bought at Payhip?

• The receipt email for the purchase includes a link. You’ll always be able to down- load the latest version of the files at that location.

• If you opted into emails while buying, you’ll get an email whenever there is new content. To opt in later, you must contact Payhip (see bottom of payhip.com).

2.2.3 Can I upgrade from package “Ebooks” to package “Ebooks + ex- ercises + quizzes”?

Yes. The instructions for doing so are on the homepage of this book.

2.3 I own the print version2.4 Notations and conventions

2.3.1 Can I get a discount for a digital version?

17

If you bought the print version, you can get a discount for a digital version. The home- page of the print version explains how.

Alas, the reverse is not possible: you cannot get a discount for the print version if you bought a digital version.

2.3.2 Can I submit an error or see submitted errors?

On the homepage of the print version, you can submit errors and see submitted errors.

2.3.3 Is there an online list with the URLs in this book?

The homepage of the print version has a list with all the URLs that you see in the footnotes of the print version.

2.4 Notations and conventions

2.4.1 What is a type signature? Why am I seeing static types in this book?

For example, you may see:

Number.isFinite(num: number): boolean

That is called the type signature of Number.isFinite(). This notation, especially the static types number of num and boolean of the result, are not real JavaScript. The notation is borrowed from the compile-to-JavaScript language TypeScript (which is mostly just JavaScript plus static typing).

Why is this notation being used? It helps give you a quick idea of how a function works. The notation is explained in detail in “Tackling TypeScript”, but is usually relatively in- tuitive.

2.4.2 What do the notes with icons mean?

Reading instructions Explains how to best read the content.

External content

Points to additional, external, content.18

2 FAQ: book and supplementary material

Tip

Gives a tip related to the current content.

Question

Asks and answers a question pertinent to the current content (think FAQ).

Warning

Warns about pitfalls, etc.

Details

Provides additional details, complementing the current content. It is similar to a footnote.

Exercise

Mentions the path of a test-driven exercise that you can do at that point.

Quiz

Indicates that there is a quiz for the current (part of a) chapter.Chapter 3

History and evolution of JavaScript

Contents

3.1 How JavaScript was created . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

3.2 Standardizing JavaScript . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

3.3 Timeline of ECMAScript versions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

3.4 Ecma Technical Committee 39 (TC39) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

3.5 The TC39 process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

3.5.1 Tip: Think in individual features and stages, not ECMAScript versions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

3.6 FAQ: TC39 process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

3.6.1 How is [my favorite proposed feature] doing? . . . . . . . . . 23

3.6.2 Is there an official list of ECMAScript features? . . . . . . . . . 23

3.7 Evolving JavaScript: Don’t break the web . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

3.1 How JavaScript was created

JavaScript was created in May 1995 in 10 days, by Brendan Eich. Eich worked at Netscape and implemented JavaScript for their web browser, Netscape Navigator.

The idea was that major interactive parts of the client-side web were to be implemented in Java. JavaScript was supposed to be a glue language for those parts and to also make HTML slightly more interactive. Given its role of assisting Java, JavaScript had to look like Java. That ruled out existing solutions such as Perl, Python, TCL, and others.

Initially, JavaScript’s name changed several times:

• Its code name was Mocha.

• In the Netscape Navigator 2.0 betas (September 1995), it was called LiveScript.

• In Netscape Navigator 2.0 beta 3 (December 1995), it got its final name, JavaScript.

1920

3.2 Standardizing JavaScript

There are two standards for JavaScript:

3 History and evolution of JavaScript

• ECMA-262 is hosted by Ecma International. It is the primary standard.

• ISO/IEC 16262 is hosted by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). This is a secondary standard.

The language described by these standards is called ECMAScript, not JavaScript. A differ- ent name was chosen because Sun (now Oracle) had a trademark for the latter name. The “ECMA” in “ECMAScript” comes from the organization that hosts the primary standard.

The original name of that organization was ECMA, an acronym for European Computer Manufacturers Association. It was later changed to Ecma International (with “Ecma” be- ing a proper name, not an acronym) because the organization’s activities had expanded beyond Europe. The initial all-caps acronym explains the spelling of ECMAScript.

In principle, JavaScript and ECMAScript mean the same thing. Sometimes the following distinction is made:

• The term JavaScript refers to the language and its implementations.

• The term ECMAScript refers to the language standard and language versions. Therefore, ECMAScript 6 is a version of the language (its 6th edition).

3.3 Timeline of ECMAScript versions

This is a brief timeline of ECMAScript versions:

• ECMAScript 1 (June 1997): First version of the standard.

• ECMAScript 2 (June 1998): Small update to keep ECMA-262 in sync with the ISO standard.

• ECMAScript 3 (December 1999): Adds many core features – “[…] regular expres- sions, better string handling, new control statements [do-while, switch], try/catch exception handling, […]”

• ECMAScript 4 (abandoned in July 2008): Would have been a massive upgrade (with static typing, modules, namespaces, and more), but ended up being too am- bitious and dividing the language’s stewards.

• ECMAScript 5 (December 2009): Brought minor improvements – a few standard library features and strict mode.

• ECMAScript 5.1 (June 2011): Another small update to keep Ecma and ISO stan- dards in sync.

• ECMAScript 6 (June 2015): A large update that fulfilled many of the promises of ECMAScript 4. This version is the first one whose official name – ECMAScript 2015 – is based on the year of publication.

• ECMAScript 2016 (June 2016): First yearly release. The shorter release life cycle resulted in fewer new features compared to the large ES6.

• ECMAScript 2017 (June 2017). Second yearly release.

• Subsequent ECMAScript versions (ES2018, etc.) are always ratified in June.3.4 Ecma Technical Committee 39 (TC39)

3.4 Ecma Technical Committee 39 (TC39)

21

TC39 is the committee that evolves JavaScript. Its members are, strictly speaking, com- panies: Adobe, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Mozilla, Opera, Twitter, and others. That is, companies that are usually fierce competitors are working together for the good of the language.

Every two months, TC39 has meetings that member-appointed delegates and invited experts attend. The minutes of those meetings are public in a GitHub repository.

3.5 The TC39 process

With ECMAScript 6, two issues with the release process used at that time became obvi- ous:

• If too much time passes between releases then features that are ready early, have to wait a long time until they can be released. And features that are ready late, risk being rushed to make the deadline.

• Features were often designed long before they were implemented and used. De- sign deficiencies related to implementation and use were therefore discovered too late.

In response to these issues, TC39 instituted the new TC39 process:

• ECMAScript features are designed independently and go through stages, starting at 0 (“strawman”), ending at 4 (“finished”).

• Especially the later stages require prototype implementations and real-world test- ing, leading to feedback loops between designs and implementations.

• ECMAScript versions are released once per year and include all features that have reached stage 4 prior to a release deadline.

The result: smaller, incremental releases, whose features have already been field-tested. Fig. 3.1 illustrates the TC39 process.

ES2016 was the first ECMAScript version that was designed according to the TC39 pro- cess.

3.5.1 Tip: Think in individual features and stages, not ECMAScript versions

Up to and including ES6, it was most common to think about JavaScript in terms of ECMAScript versions – for example, “Does this browser support ES6 yet?”

Starting with ES2016, it’s better to think in individual features: once a feature reaches stage 4, you can safely use it (if it’s supported by the JavaScript engines you are targeting). You don’t have to wait until the next ECMAScript release.

3.6 FAQ: TC39 process22

3 History and evolution of JavaScript

Figure 3.1: Each ECMAScript feature proposal goes through stages that are numbered from 0 to 4. Champions are TC39 members that support the authors of a feature. Test 262 is a suite of tests that checks JavaScript engines for compliance with the language specification.3.7 Evolving JavaScript: Don’t break the web

3.6.1 How is [my favorite proposed feature] doing?

23

If you are wondering what stages various proposed features are in, consult the GitHub repository proposals.

3.6.2 Is there an official list of ECMAScript features?

Yes, the TC39 repo lists finished proposals and mentions in which ECMAScript versions they were introduced.

3.7 Evolving JavaScript: Don’t break the web

One idea that occasionally comes up is to clean up JavaScript by removing old features and quirks. While the appeal of that idea is obvious, it has significant downsides.

Let’s assume we create a new version of JavaScript that is not backward compatible and fix all of its flaws. As a result, we’d encounter the following problems:

• JavaScript engines become bloated: they need to support both the old and the new version. The same is true for tools such as IDEs and build tools.

• Programmers need to know, and be continually conscious of, the differences be- tween the versions.

• You can either migrate all of an existing code base to the new version (which can be a lot of work). Or you can mix versions and refactoring becomes harder because you can’t move code between versions without changing it.

• You somehow have to specify per piece of code – be it a file or code embedded in a web page – what version it is written in. Every conceivable solution has pros and cons. For example, strict mode is a slightly cleaner version of ES5. One of the reasons why it wasn’t as popular as it should have been: it was a hassle to opt in via a directive at the beginning of a file or a function.

So what is the solution? Can we have our cake and eat it? The approach that was chosen for ES6 is called “One JavaScript”:

• New versions are always completely backward compatible (but there may occa- sionally be minor, hardly noticeable clean-ups).

• Old features aren’t removed or fixed. Instead, better versions of them are intro- duced. One example is declaring variables via let – which is an improved version of var.

• If aspects of the language are changed, it is done inside new syntactic constructs. That is, you opt in implicitly. For example, yield is only a keyword inside gen- erators (which were introduced in ES6). And all code inside modules and classes (both introduced in ES6) is implicitly in strict mode.

Quiz

See quiz app.24

3 History and evolution of JavaScriptChapter 4

New JavaScript features

Contents

4.1 New in ECMAScript 2022 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

4.2 New in ECMAScript 2021 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

4.3 New in ECMAScript 2020 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

4.4 New in ECMAScript 2019 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

4.5 New in ECMAScript 2018 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

4.6 New in ECMAScript 2017 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

4.7 New in ECMAScript 2016 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

4.8 Source of this chapter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

This chapter lists what’s new in ES2016–ES2022 in reverse chronological order. It starts after ES2015 (ES6) because that release has too many features to list here.

4.1 New in ECMAScript 2022

ES2022 will probably become a standard in June 2022. The following proposals have reached stage 4 and are scheduled to be part of that standard:

• New members of classes:

– Properties (public slots) can now be created via:

* Instance public fields

* Static public fields

– Private slots are new and can be created via:

* Private fields (instance private fields and static private fields)

* Private methods and accessors (non-static and static)

– Static initialization blocks

• Private slot checks (“ergonomic brand checks for private fields”): The following expression checks if obj has a private slot #privateSlot:

#privateSlot in obj

2526

4 New JavaScript features

• Top-level await in modules: We can now use await at the top levels of modules and don’t have to enter async functions or methods anymore.

• error.cause: Error and its subclasses now let us specify which error caused the current one:

new Error('Something went wrong', {cause: otherError})

• Method .at() of indexable values lets us read an element at a given index (like the bracket operator []) and supports negative indices (unlike the bracket operator).

> ['a', 'b', 'c'].at(0)

'a'

> ['a', 'b', 'c'].at(-1)

'c'

The following “indexable” types have method .at():

– string

– Array

– All Typed Array classes: Uint8Array etc.

• RegExp match indices: If we add a flag to a regular expression, using it produces match objects that record the start and end index of each group capture.

• Object.hasOwn(obj, propKey) provides a safe way to check if an ob- ject obj has an own property with the key propKey. In contrast to Ob- ject.prototype.hasOwnProperty, it works with all objects.

More features may still be added to ES2022

If that happens, this book will be updated accordingly.

4.2 New in ECMAScript 2021

The following features were added in ECMAScript 2021:

• String.prototype.replaceAll() lets us replace all matches of a regular expres- sion or a string (.replace() only replaces the first occurrence of a string):

> 'abbbaab'.replaceAll('b', 'x')

'axxxaax'

• Promise.any() and AggregateError: Promise.any() returns a Promise that is ful- filled as soon as the first Promise in an iterable of Promises is fulfilled. If there are only rejections, they are put into an AggregateError which becomes the rejection value.

We use Promise.any() when we are only interested in the first fulfilled Promise among several.

• Logical assignment operators:27

4.3 New in ECMAScript 2020

a ||= b

a &&= b

a ??= b

• Underscores (_) as separators in:

– Number literals: 123_456.789_012

– Bigint literals: 6_000_000_000_000_000_000_000_000n

• WeakRefs: This feature is beyond the scope of this book. For more information on it, see its proposal.

4.3 New in ECMAScript 2020

The following features were added in ECMAScript 2020:

• New module features:

– Dynamic imports via import(): The normal import statement is static: We can only use it at the top levels of modules and its module specifier is a fixed string. import() changes that. It can be used anywhere (including condi- tional statements) and we can compute its argument.

– import.meta contains metadata for the current module. Its first widely sup- ported property is import.meta.url which contains a string with the URL of the current module’s file.

– Namespace re-exporting: The following expression imports all exports of module 'mod' in a namespace object ns and exports that object.

export * as ns from 'mod';

• Optional chaining for property accesses and method calls. One example of op- tional chaining is:

value.?prop

This expression evaluates to undefined if value is either undefined or null. Oth- erwise, it evaluates to value.prop. This feature is especially useful in chains of property reads when some of the properties may be missing.

• Nullish coalescing operator (??):

value ?? defaultValue

This expression is defaultValue if value is either undefined or null and value otherwise. This operator lets us use a default value whenever something is miss- ing.

Previously the Logical Or operator (||) was used in this case but it has down- sides here because it returns the default value whenever the left-hand side is falsy (which isn’t always correct).

• Bigints – arbitrary-precision integers: Bigints are a new primitive type. It supports integer numbers that can be arbitrarily large (storage for them grows as necessary).28

4 New JavaScript features

• String.prototype.matchAll(): This method throws if flag /g isn’t set and returns an iterable with all match objects for a given string.

• Promise.allSettled() receives an iterable of Promises. It returns a Promise that is fulfilled once all the input Promises are settled. The fulfillment value is an Array with one object per input Promise – either one of:

– { status: 'fulfilled', value: «fulfillment value» }

– { status: 'rejected', reason: «rejection value» }

• globalThis provides a way to access the global object that works both on browsers and server-side platforms such as Node.js and Deno.

• for-in mechanics: This feature is beyond the scope of this book. For more infor- mation on it, see its proposal.

4.4 New in ECMAScript 2019

The following features were added in ECMAScript 2019:

• Array method .flatMap() works like .map() but lets the callback return Arrays of zero or more values instead of single values. The returned Arrays are then con- catenated and become the result of .flatMap(). Use cases include:

– Filtering and mapping at the same time

– Mapping single input values to multiple output values

• Array method .flat() converts nested Arrays into flat Arrays. Optionally, we can tell it at which depth of nesting it should stop flattening.

• Object.fromEntries() creates an object from an iterable over entries. Each entry is a two-element Array with a property key and a property value.

• String methods: .trimStart() and .trimEnd() work like .trim() but remove whitespace only at the start or only at the end of a string.

• Optional catch binding: We can now omit the parameter of a catch clause if we don’t use it.

• Symbol.prototype.description is a getter for reading the description of a symbol. Previously, the description was included in the result of .toString() but couldn’t be accessed individually.

These new ES2019 features are beyond the scope of this book:

• JSON superset: See 2ality blog post.

• Well-formed JSON.stringify(): See 2ality blog post.

• Function.prototype.toString() revision: See 2ality blog post.

4.5 New in ECMAScript 2018

The following features were added in ECMAScript 2018:4.5 New in ECMAScript 2018

29

• Asynchronous iteration is the asynchronous version of synchronous iteration. It is based on Promises:

– With synchronous iterables, we can immediately access each item. With asyn- chronous iterables, we have to await before we can access an item.

– With synchronous iterables, we use for-of loops. With asynchronous iter- ables, we use for-await-of loops.

• Spreading into object literals: By using spreading (...) inside an object literal, we can copy the properties of another object into the current one. One use case is to create a shallow copy of an object obj:

const shallowCopy = {...obj};

• Rest properties (destructuring): When object-destructuring a value, we can now use rest syntax (...) to get all previously unmentioned properties in an object.

const {a, ...remaining} = {a: 1, b: 2, c: 3}; assert.deepEqual(remaining, {b: 2, c: 3});

• Promise.prototype.finally() is related to the finally clause of a try-catch- finally statement – similarly to how the Promise method .then() is related to the try clause and .catch() is related to the catch clause.

On other words: The callback of .finally() is executed regardless of whether a Promise is fulfilled or rejected.

• New Regular expression features:

– RegExp named capture groups: In addition to accessing groups by number, we can now name them and access them by name:

const matchObj = '---756---'.match(/(?<digits>[0-9]+)/) assert.equal(matchObj.groups.digits, '756');

– RegExp lookbehind assertions complement lookahead assertions:

* Positive lookbehind: (?<=X) matches if the current location is preceded

by 'X'.

* Negative lookbehind: (?<!X) matches if the current location is not pre- ceded by '(?<!X)'.

– s (dotAll) flag for regular expressions. If this flag is active, the dot matches line terminators (by default, it doesn’t).

– RegExp Unicode property escapes give us more power when matching sets of Unicode code points – for example:

> /^\p{Lowercase_Letter}+$/u.test('aüπ')

true

> /^\p{White_Space}+$/u.test('\n \t')

true

> /^\p{Script=Greek}+$/u.test('ΩΔΨ')

true30

4 New JavaScript features

• Template literal revision allows text with backslashes in tagged templates that is illegal in string literals – for example:

windowsPath`C:\uuu\xxx\111` latex`\unicode`

4.6 New in ECMAScript 2017

The following features were added in ECMAScript 2017:

• Async functions (async/await) let us use synchronous-looking syntax to write asynchronous code.

• Object.values() returns an Array with the values of all enumerable string-keyed properties of a given object.

• Object.entries() returns an Array with the key-value pairs of all enumerable string-keyed properties of a given object. Each pair is encoded as a two-element Array.

• String padding: The string methods .padStart() and .padEnd() insert padding text until the receivers are long enough:

> '7'.padStart(3, '0')

'007'

> 'yes'.padEnd(6, '!')

'yes!!!'

• Trailing commas in function parameter lists and calls: Trailing commas have been allowed in Arrays literals since ES3 and in Object literals since ES5. They are now also allowed in function calls and method calls.

• The following two features are beyond the scope of this book:

– Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors() (see “Deep JavaScript”)

– Shared memory and atomics (see proposal)

4.7 New in ECMAScript 2016

The following features were added in ECMAScript 2016:

• Array.prototype.includes() checks if an Array contains a given value.

• Exponentiation operator (**):

> 4 ** 2

16

4.8 Source of this chapter

ECMAScript feature lists were taken from the TC39 page on finished proposals.Chapter 5

FAQ: JavaScript

Contents

5.1 What are good references for JavaScript? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

5.2 How do I find out what JavaScript features are supported where? . . 31

5.3 Where can I look up what features are planned for JavaScript? . . . 32

5.4 Why does JavaScript fail silently so often? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

5.5 Why can’t we clean up JavaScript, by removing quirks and outdated features? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

5.6 How can I quickly try out a piece of JavaScript code? . . . . . . . . . 32

5.1 What are good references for JavaScript?

Please consult §6.3 “JavaScript references”.

5.2 How do I find out what JavaScript features are sup- ported where?

This book usually mentions if a feature is part of ECMAScript 5 (as required by older browsers) or a newer version. For more detailed information (including pre-ES5 ver- sions), there are several good compatibility tables available online:

• ECMAScript compatibility tables for various engines (by kangax, webbedspace, zloirock)

• Node.js compatibility tables (by William Kapke)

• Mozilla’s MDN web docs have tables for each feature that describe relevant ECMA- Script versions and browser support.

• “Can I use…” documents what features (including JavaScript language features) are supported by web browsers.

3132

5 FAQ: JavaScript

5.3 Where can I look up what features are planned for JavaScript?

Please consult the following sources:

• §3.5 “The TC39 process” describes how upcoming features are planned.

• §3.6 “FAQ: TC39 process” answers various questions regarding upcoming features.

5.4 Why does JavaScript fail silently so often?

JavaScript often fails silently. Let’s look at two examples.

First example: If the operands of an operator don’t have the appropriate types, they are converted as necessary.

> '3' * '5'

15

Second example: If an arithmetic computation fails, you get an error value, not an excep- tion.

>1/0

Infinity

The reason for the silent failures is historical: JavaScript did not have exceptions until ECMAScript 3. Since then, its designers have tried to avoid silent failures.

5.5 Why can’t we clean up JavaScript, by removing quirks and outdated features?

This question is answered in §3.7 “Evolving JavaScript: Don’t break the web”.

5.6 How can I quickly try out a piece of JavaScript code?

§8.1 “Trying out JavaScript code” explains how to do that.Part II First steps

33Chapter 6

Using JavaScript: the big picture

Contents

6.1 What are you learning in this book? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

6.2 The structure of browsers and Node.js . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

6.3 JavaScript references . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

6.4 Further reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

In this chapter, I’d like to paint the big picture: what are you learning in this book, and how does it fit into the overall landscape of web development?

6.1 What are you learning in this book?